One Of The Worst Endings In Videogame History

Well, folks, it’s December 23rd, and both Christmas and Channukah are right around the corner. Sounds like it’s the perfect time to talk about a game that takes place on the Day of the Dead. I mean, it’s kinda topical – the remastered version of Full Throttle was shown off at The Game Awards a couple weeks back, which means Tim Schafer’s in the news again, which means everyone’s talking about what many see as his greatest achievement – 1998’s Grim Fandango, which got a remastered release of its own last year. People really like Grim Fandango, and you know what that means – it’s time to give it a Second Opinion.

I had a somewhat different experience with Grim Fandango than that of many of our viewers – I didn’t play it until the remastered edition came out last year. (By the way, commenters, you’re welcome – now you have a reason to discredit my whole opinion on the game offhand.) I’d heard about it, of course – as an avid lover of Sam & Max, Zak McKraken, and above all, Monkey Island, I’d often heard about how they all paled in comparison to Tim Schafer’s magnum opus about love, death, and the afterlife. And then I played it, and I realized the truth about the game: whenever people talk about how good it is, they’re really only talking about the second chapter.

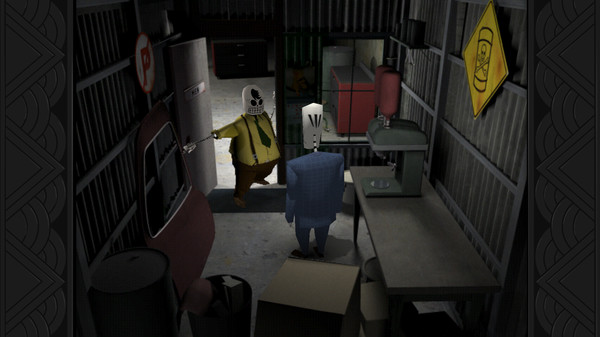

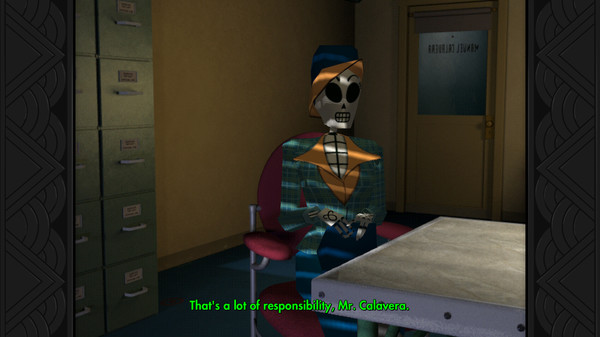

Oh, perhaps that’s unfair. The other chapters have good moments, like the introduction to Glottis in year one or the rooftop chase in year four or, uh…something in year three, give me a minute, I’m sure there was something cool. And the whole game is gorgeous, even with the limitations of what 3D looked like in the 1990s. The mixture of film noir, Mexican calaca figures, and art deco is something truly unique, not just in the world of games, but in the world of entertainment media. The game’s character designs are some of the best and most interesting I’ve ever seen, and Peter McConnell’s legendary soundtrack also helps to set the tone and setting apart from other games. It was a revelation to play in 2015 – I can only imagine what it was like 17 years prior.

Unfortunately, other than in that Year 2 section, Grim Fandango’s story and gameplay never quite deliver on the promise of its setting. By the way, I should probably say that since Second Opinion is a critical analysis series, not a review series, this feature is going to contain major plot spoilers. So if you haven’t played the game and want to, go pick it up in the Steam sale and then come back.

OK, now that you’re back, where should we begin. How about gameplay. Grim Fandango often gets praised for its puzzle design, because unlike other adventure games where the puzzles are basically gates you have to pass to get back to the story, which is what you actually care about, it artfully weaves its puzzles and its story together. Y’know, like when you have to stuff packing materials into balloons to break the central communications chamber! Or when you have to steal pigeon’s eggs. Oh, right. This is one of those things that’s only true of the second section, where the goal of getting onto a ship blossoms into interactions with a variety of fascinating characters and a surprisingly deep story about corruption and intrigue within the afterlife. For the rest of the game the puzzles are just as nonsensical and meaningless as they are in every other adventure game. And even in Year 2, there’s missteps, like when a puzzle makes you use Lola’s tragic death to blackmail her murderer into giving you his tools. Tools, Manny? Really? She poured her heart and soul out to you and all you can think about is doing a little woodwork?

And the puzzles themselves are so badly designed. See, one thing Tim Schafer doesn’t get (in any of his games) is that a good puzzle is one where once you’ve figured out how to do it you can do it instantly. The most legendary example of him breaking this rule in Fandango is the beaver puzzle. So let me lay this out for you: you have to get past these fire beavers, which exist, for some reason, and you have to lure them into position with a bone and then spray them with a fire extinguisher. Now that sequence of actions isn’t too hard to figure out, if you’re used to nonsensical adventure game logic, but then you have to go to a screen there’s no indication of you being able to go to, stand in a very specific spot that isn’t marked in any way, and perfectly time the spray. If you screw up any of these steps, you have to walk Manny’s incredibly slow butt back to the bridge to get more bones. And then, best of all, even after you’ve done it once you still have to do the exact same thing two more times. Yo, Tim? This isn’t fun, and sure as hell doesn’t add anything to the story, and why in the name of Guybrush Threepwood would you make me do it three times? The puzzle’s been solved, now you’re just artificially padding out the runtime and difficulty of your crappy game.

And that puzzle wouldn’t be nearly as frustrating if it weren’t for how bad the controls are. Yeah, I know everyone always rags on the tank controls, but there’s good reason for it. I don’t know what it is about adventure games. Getting an adventure game control scheme right is the easiest thing in the world – there’s a reason we call them “point and clicks”. That’s all it should ever have to be. Heck, say what you will about verb boxes taking up half the screen, but at least you could easily do whatever it is you wanted to do. But no, instead we have Tales of Monkey Island’s weird arrow thing, or Day of the Tentacle Remastered’s scroll wheel, or Grim Fandango’s awful tank controls. I know it’s supposed to be more “immersive”, make you feel like you’re really controlling a real person, but you know what’s really immersive? Gameplay that’s fun and fluid and doesn’t make me start cursing at my computer because I walked into an area and Manny turned around and walked back into the last area because the camera moved. I mean, you have to use the “Page Up” and “Page Down” keys to scroll through your inventory – the only reason I should ever use those buttons is if I accidentally missed when trying to hit “end.”

Now, these might seem like nitpicks, but it’s the small things that make or break a game, especially one like this that’s trying to get by mainly on “feel” and the emotional connection you make to the world. And it’s the small things that Grim Fandango gets wrong, over and over again, until you either have to be blinded by nostalgia or really trying to like the game despite its many faults. That beaver puzzle’s the worst, but like I said, many of the puzzles are similarly frustrating or require similarly pointless repetition. Besides the controls, the game’s riddled with technical issues, even in its remastered version, which reminds you at the beginning to save frequently because it crashes so often and Double Fine couldn’t be bothered to put in an autosave.

And then there’s the story, which is riddled with problems. It starts nicely, with an interesting look into the world of afterlife travel agents that develops into an intriguing mystery with plenty of nods to Casablanca, but then the developers realized there were two more years in this four-year journey to the afterlife and the plot goes completely off the rails. What the hell was that whole section with the coral mining plant? You could’ve taken all that out and lost nothing.

See, good stories follow the rule of One Big Lie. This means that you can suspend audience’s disbelief for one big lie which everything else should logically follow. Grim Fandango’s one big lie is its setting, a world where death turns you into a skeleton and you have to get to the Ninth Underworld, essentially heaven, either by taking a four-year journey or by traveling there instantly on the Number Nine train, depending on how good you were in life. Setting details that develop logically from this One Big Lie work really well, like the idea of “sprouting”, where skeletons get shot with a type of fertilizer that makes flowers grow through their bones. It doesn’t “kill” them, technically, but they’re trapped forever in that state. This is a great idea, because it allows you to have death in a world where characters are already dead, both the nature of sprouting and the fact that humans have found a way to kill other humans even in the afterlife makes sense in the context of the rest of the story, and it leads to some really poignant visuals, like Lola turning into flowers and flying away, or the final showdown taking place in the villain’s greenhouse.

But the coral mining plant has nothing to do with anything, as does the whole concept of the Edge of the World. Neither does Manny’s job – if the rate at which you reach the Ninth Underworld depends on how good you were in life, what can he do to upsell you and convince you to buy better travel packages? There’s a throwaway line about “the money you were buried with”, but being buried with more than two coins isn’t a common practice, certainly not common enough to support the big business the Department of Death apparently is. And why does the game start with his boss being mad at his not having good clients? Isn’t that completely random? And what about the beginning of the last chapter, where Glottis is about to die because his purpose was to travel at high speeds and he’s spent the last year walking? Because if that were true, wouldn’t he have been dying at the end of chapter 2, when he’s been spending the last year playing piano in a bar? The entire setup for the last act of the game is based on something that’s never been mentioned before.

Which brings us to the worst, most insulting part of Grim Fandango’s ham-fisted story: its ending (major spoilers obviously follow.) The ending of Grim Fandango, like the ending of LeChuck’s Revenge, another Tim Schafer joint, ruins what made the game before it good. So, one of the best parts of the game is Hector LaMans, the Sydney-Greenstreet-inspired, scene-chewing boss of the afterlife’s criminal underworld. He’s compelling, he’s brilliantly performed by Jim Ward, so obviously his final showdown has to be something classic, right? Something like the end of Secret of Monkey Island, where the final puzzle is a fast-paced showdown with a tough and obviously far more dangerous enemy? Well, no, because as previously stated, puzzle-story interaction isn’t how Grim Fandango do. Instead, you shoot a pipe and Hector dies off-screen. His last words are “arghh arggh ahhh.”

And that’s not even the worst part. I could live with that – there’s something to be said for giving a villain who loves the spotlight no dignity in death, even though I highly doubt the ending was motivated by anything other than being too lazy or too over-budget to animate a death scene. But then there’s the bit after. The whole time the game’s story has been carefully reminding you of a fact most other adventure games expect you to forget: the protagonist is a terrible person. Not only is there frequent mention of his owing some kind of ill-defined debt to the powers that be, but Meche’s capture by Hector and involvement with the criminal underworld (haha) is entirely his fault, as are a lot of the other bad things that happen in the story. He neglects people who care about him in pursuit of his singular goal, because like all great film noir heroes you get the sense that Manny isn’t a good guy, he’s just being bad in the right direction. And that’s why the story ends with him being denied passage to the Ninth Underworld, and instead staying behind with his best friend, Glottis, watching the girl he loves leave for safety and happiness in one last well-executed nod to Casablanca.

Oh, wait, no – actually, he gets to leave on the Number Nine as well, because I guess doing terrible things that work out for good in the end covers for a lifetime of misdeeds? And the ticket was given to him by the Department of Death, even though it was super corrupt and everyone there hated him and all of the people who were in charge there died? Oh, and Glottis still can’t go into the Ninth Underworld, which earlier made is so that Manny didn’t want to go, but now I guess he just doesn’t care? And all of this is rushed into the space of two minutes. I will seriously never get over how bad the ending of Grim Fandango is. I mean, like I said, all they had to do was rip off Casablanca like they did for the rest of the game! How is Schafer so bad at ending stories?

But here’s the thing – this terrible, terrible ending is often praised by game critics. Why? Because it ends on what even I have to admit is a really good line and a really cool visual of the train disappearing into a temple while the skeletal mariachis play on. And that’s the problem with Grim Fandango. I could go on for hours listing more plot holes or frustrating puzzles, but the game hopes that you won’t pay attention to that because, hey, isn’t this cutscene really pretty and poignant? Isn’t this music really good? It’s the definition of style over substance, an absolute mess of a game that carries itself with enough style that people laud it as a brilliant artistic and philosophical work.

Look, don’t get it twisted – I like Grim Fandango. Really, my problem with it is the same problem I had with Day of the Tentacle – both of them are merely good games that get held up as great games. Every time someone makes a best games list or a best stories in games list, there’s Grim Fandango, with its crappy ending and its shark-jumping third act. And sure, when it came out I’ve no doubt Grim Fandango was probably the best story any videogame had, but I just wish we could get rid of the nostalgia from that time period and look at modern games with good stories. Those lists should be populated with things like The Walking Dead, The Beginner’s Guide, or Undertale, not this charming but ultimately pulpy story that isn’t written half as well.

And that’s my professional opinion.